History

How we got here from there.

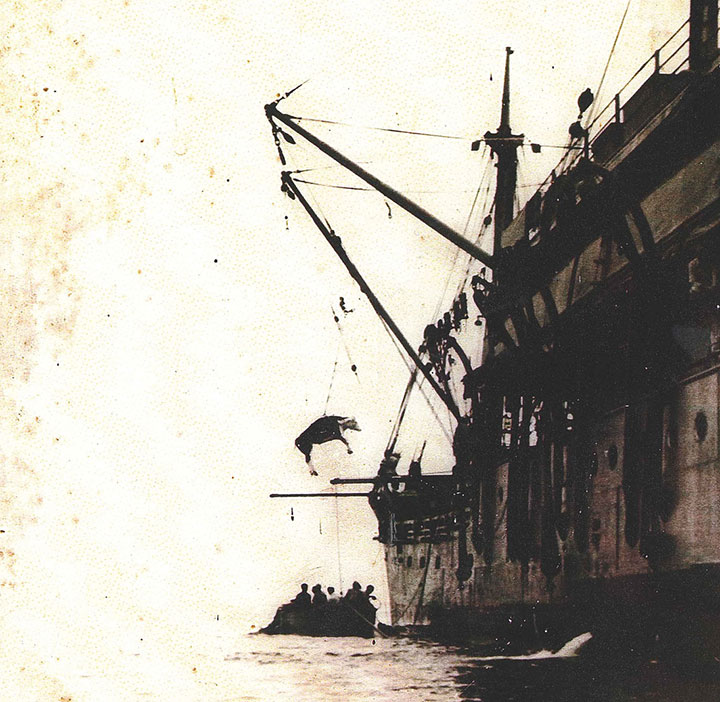

The Chinese migration to the Kingdom of Hawaii was not undertaken lightly.

Why leave China?

Throughout their long history, the Chinese have been incredibly devoted to tradition and place. The villages of Kung Sheong Doo where our ancestors were born have been the home towns of our families for hundreds of years. In most cases, we can still find relatives–near and distant cousins–with our same surname living in the village.

In a perfect world, a Chinese family would never willingly send their sons and heirs to live and work in a foreign land apart from the clan. In a perfect world, each male child was a precious treasure who was duty-bound to study hard, work hard, bring honor to the family, attend to the worship of the ancestors, marry a suitable bride and produce another generation of sons to carry on the family name.

But in the mid-1800s in China, it was not a perfect world. Wars, pestilence, drought, famine, political upheavals, and a collapsing economy all combined to force families to make an incredibly hard decision. Send the sons outside of China to earn money for the family, or face starvation and death. Outside money was the only hope of keeping the family alive until China could recover.

Learn more about the migration to Hawaii >

Earning money in Hawaii

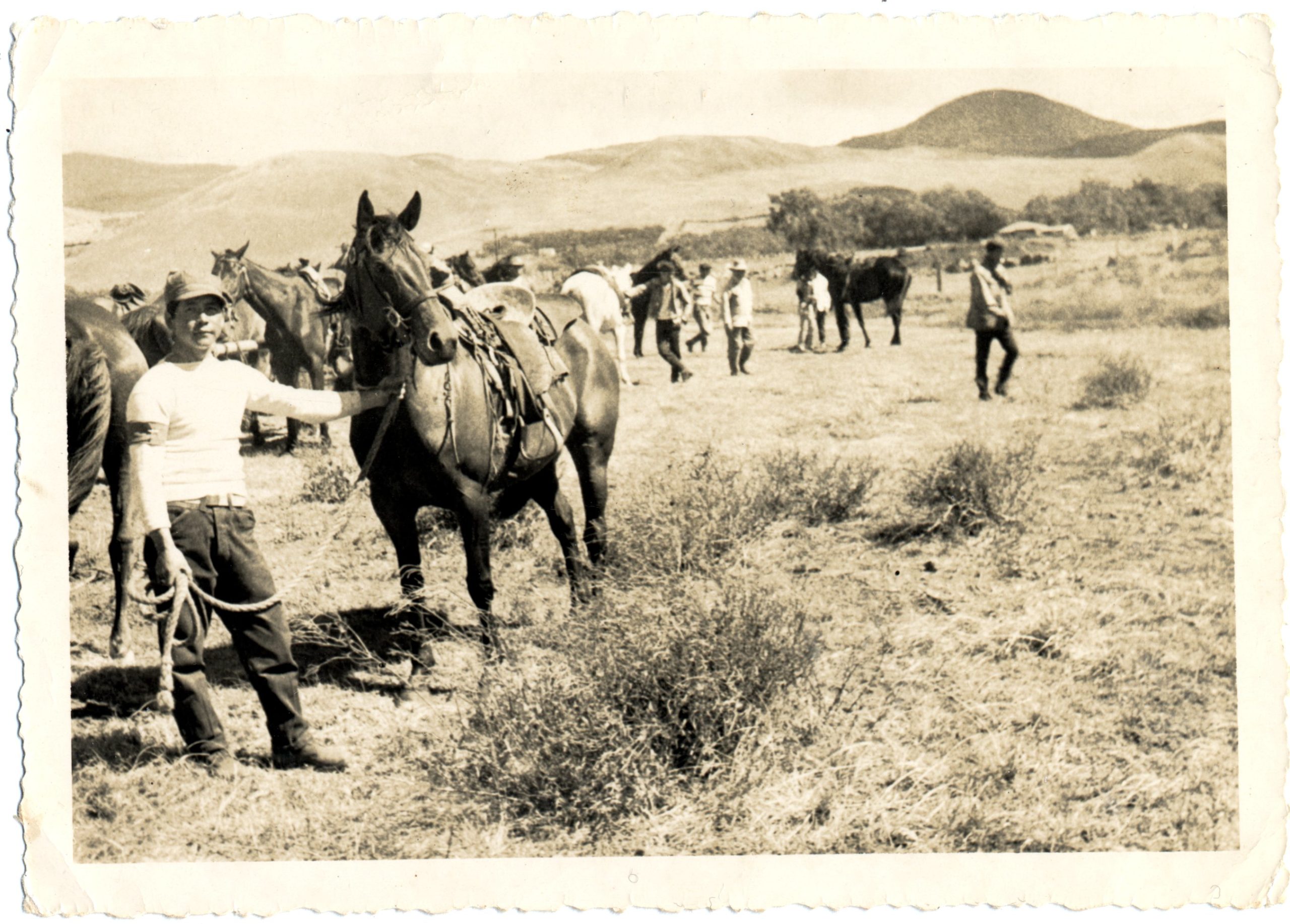

Depending on their family’s situation, the opportunities for earning money in the Kingdom of Hawaii, and later the Territory of Hawaii, ranged from back-breaking contract labor on a sugar plantation, to life as a paniolo (cowboy) caring for the king’s cattle, to work in services like food service, laundry service, and much more — with a lot of variations in pay, working conditions, and physical comfort.

Although they may have started at the bottom of the socio-economic ladder, their extraordinary work ethic and commitment to the needs of their families enabled many of them to achieve great success over a lifetime in the islands.

The story of Tong Yee Aii唐綺, Alai Aii, and Wong Kun Akana黃根

Tong Yee Aii was the grandfather of Tong Phong who opened the first Chinese bank in Hawaii and spent most of his wealth to help Sun Yat Sen.

Aii was born in Tangjia Village in 1820, married to Miss She of Guan Tang, and had a son named Tong Chong. Tong Yee left his wife, son, and hometown to pan for gold in San Francisco in 1849, and arrived in Hilo in 1850.

To help benefit his sugar plantation business, he married a Hawaiian woman like many of the local Chinese did. His wife, Kahaole’au’a (1835-1882), was the daughter of a Hawaiian chief.

Tong Yee became known as a sugar master in the local Hilo area. Due to skillful and excellent management, the sugar plantation developed and prospered. Tong Yee and his wife built a house in Kukuau, on two acres of land.

Gu Chuan Pin 古傳品 Migrates to Hawaii and Changes History

Gu Chuan Pin 古傳品 was one of the early immigrants from the Nazhou Gu clan who settled in Hawaii. His family’s experiences in Hawaii and later in Chicago, Illinois are fascinating, because they are tied closely to the political affairs of China.

Gu Chuan Pin’s ninth child, Margaret, wrote the family history, called Thank You Father, by Aunt Margaret. It is filled with fascinating details about growing up in a transplanted Chinese family in Hawaii in a family of 12 children.

This family’s story becomes an important lens through which you can see how it was to live as a Chinese immigrant in Hawaii during the tumultuous years when China was throwing off Imperialism, Hawaii was changing from a monarchy to a United States Territory, the Spanish Flu pandemic raged across the world, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, and America was coming to grips with its deep-rooted racial bias and systematic oppression of the Chinese.